Text

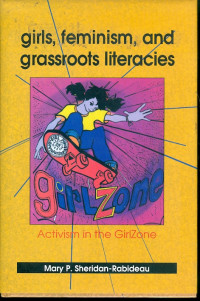

Girls, feminism, and grassroots literacies-Activism in the GirlZone

This book explores the rise and fall of a grassroots, girl-centered organization, GirlZone, which sought to make social change on a local level. Whether skateboarding or designing Web pages, celebrating in weekend “GrrrlFests” or producing a biweekly RadioGirl program, participants in GirlZone came to understand themselves as competent actors in a variety of activities they had previously thought were closed off to them. Drawing on six years of fieldwork examining GirlZone from its inception until its demise, Mary P. Sheridan-Rabideau offers insights on the current state of and study of literacy in the extracurriculum. She addresses how girls have become cultural flashpoints reflecting societal—and particularly feminist—anxieties and hopes about the present and the future. Sheridan-Rabideau does more than chronicle the pressure girls face; she offers advice on how feminists, cultural critics, and activists can effect social change on local levels, even in today’s increasingly globalized contexts. Girls, Feminism, and Grassroots Literacies carried me down a road where all of my varied identities collided. As a feminist, a sociologist, a professor, a past coordinator of a social entrepreneurship program, and most importantly, as a mother of two daughters (ages seven and one), I found myself pulling significant portions of the story Sheridan-Rabideau conveys into each portion of my lived experience. I also found myself struggling to find answers to some of the pressing questions she raises, which were pivotal to the evolution of GirlZone and, I would argue, remain persistent concerns for feminist pedagogies in general. Girls, Feminism, and Grassroots Literacies is the culmination of over five years of ethnographic research with a local group of feminist activists in Champaign-Urbana, Illinois, who focused their energies on strengthening identity development and opportunity access for girls in their community. Their primary means of providing an outlet for this mission was to create an organization called GirlZone in 1996 that offered weekly workshops on a wide variety of topics “to explore and celebrate girls’ abilities and skills” (15). Sheridan-Rabideau also conducts close textual analyses of books, magazines, music, and other resources that emerged alongside of (or in response to) heightened interest in girls and girl culture. Sometimes these literacies enabled the growth of girl culture and girl power, while other times they presented contradictory and challenging messages that hampered the reach of organizations such as GirlZone. Sheridan-Rabideau carries the reader on a journey through the creation and evolution of GirlZone and the varied struggles along the way. One almost feels voyeuristic, peering into the lives of the women and girls who were committed to the “feminist pedagogies” (80) central to the mission of the organization. Their struggles arose on numerous fronts. One involved where to seek funding—is it more important ultimately to receive funding to sustain the organization even if it means crafting a grant proposal that is only tangentially related to the core mission of the organization, or is it crucial to remain true to the organization’s core values and not “sell out” (127)? Ultimately, the leaders of GirlZone believed it was far more important to remain true to the feminist values that brought them together at the outset, but unfortunately, this stance significantly limited their access to funding and resulted in the dissolution of GirlZone. A second significant struggle for these young activists involved how to reconcile differences in feminist pedagogies that existed among those intimately involved with the organization—what happens when the leaders of GirlZone, and another group that grew out of GirlZone called Radio Girls, have contradictory opinions about making feminism and a “do it yourself” modus operandi the driving force of the group’s activities? Unfortunately, this conflict also contributed to the termination of GirlZone and Radio Girls for two reasons. First, the leaders found it too difficult to reconcile their own differences and continue to follow a common mission. Second, the girls (typically ages six to twelve) were torn between the desire to be involved with activities that provided a way for them to develop their own social identities (89) outside of the confines of traditional public pedagogies for girls and a desire not to be overtly identified with the label “feminist” because of the negative subterranean values associated with the term. Thus, the leaders moved on to other professional opportunities, and the girls chose to find other outlets for their interests in feminist pedagogies that were more comfortable to them. These struggles are not unique to GirlZone, and perhaps as I read the book, the revelation of conflicts and the final question of “what is success” (149) were the most instructive components of the work. While the writing style used in the text is very complex (and for that reason, I would not recommend this text for use in an undergraduate course), the story is tremendously illustrative of the constant questions that feminists face daily. In this time of Third Wave feminism, there are many Second Wave feminists searching for a way to remain involved in the movement without feeling alienated because they prefer at times not to be as bold with their feminisms as their.

Availability

| KP.II-00023 | KP.II MAR g | My Library | Available |

Detail Information

- Series Title

-

-

- Call Number

-

KP.II SHER g

- Publisher

- New York : State University of New York Press., 2008

- Collation

-

xii, 204 hlm. ; 23 cm.

- Language

-

English

- ISBN/ISSN

-

978-0-7914-7297-2

- Classification

-

KP.II

- Content Type

-

-

- Media Type

-

-

- Carrier Type

-

-

- Edition

-

-

- Subject(s)

- Specific Detail Info

-

Series in Feminist Critism and Theory

- Statement of Responsibility

-

-

Other version/related

No other version available

File Attachment

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment

Computer Science, Information & General Works

Computer Science, Information & General Works  Philosophy & Psychology

Philosophy & Psychology  Religion

Religion  Social Sciences

Social Sciences  Language

Language  Pure Science

Pure Science  Applied Sciences

Applied Sciences  Art & Recreation

Art & Recreation  Literature

Literature  History & Geography

History & Geography