Text

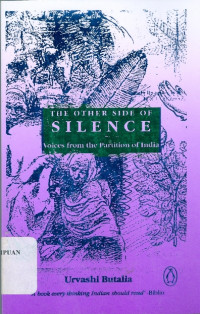

The other Side of Silence: Voices From The Partition of India

The political partition of India caused one of the great human convulsions of history. Never before or since have so many people exchanged their homes and countries so quickly. In the space of a few months, about twelve million people moved between the new, truncated India and the two wings, East and West, of the newly created Pakistan. By far the largest proportion of these refugees—more than ten million of them—crossed the western border which divided the historic state of Punjab, Muslims travelling west to Pakistan, Hindus and Sikhs east to India. Slaughter sometimes accompanied and sometimes prompted their movement; many others died from malnutrition and contagious diseases. Estimates of the dead vary from 200,000 (the contemporary British figure) to two million (a later Indian estimate) but that somewhere around a million people died is now widely accepted. As always there was widespread sexual savagery: about 75,000 women are thought to have been abducted and raped by men of religions different from their own (and indeed sometimes by men of their own religion). Thousands of families were divided, homes destroyed, crops left to rot, villages abandoned. Astonishingly, and despite many warnings, the new governments of India and Pakistan were unprepared for the convulsion: they had not anticipated that the fear and uncertainty created by the drawing of borders based on headcounts of religious identity—so many Hindus versus so many Muslims—would force people to flee to what they considered `safer' places, where they would be surrounded by their own kind. People travelled in buses, in cars, by train, but mostly on foot in great columns called kafilas, which could stretch for dozens of miles. The longest of them, said to comprise nearly 400,000 people, refugees travelling east to India from western Punjab, took as many as eight days to pass any given spot on its route.

This is the generality of Partition: it exists publicly in history books. The particular is harder to discover; it exists privately in the stories told and retold inside so many households in India and Pakistan. I grew up with them: like many Punjabis of my generation, I am from a family of Partition refugees. Memories of Partition, the horror and brutality of the time, the harkening back to an—often mythical—past where Hindus and Muslims and Sikhs lived together in relative peace and harmony, have formed the staple of stories I have lived with. My mother and father come from Lahore, a city loved and sentimentalized by its inhabitants, which lies only twenty miles inside the Pakistan border. My mother tells of the dangerous journeys she twice made back there to bring her younger brothers and sister to India. My father remembers fleeing Lahore to the sound of guns and crackling fire. I would listen to these stories with my brothers and sister and hardly take them in. We were middle-class Indians who had grown up in a period of relative calm and prosperity, when tolerance and `secularism' seemed to be winning the argument. These stories—of loot, arson, rape, murder—came out of a different time. They meant little to me.

Then, in October 1984, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her security guards, both Sikhs. For days afterwards Sikhs all over India were attacked in an orgy of violence and revenge. Many homes were destroyed and thousands died. In the outlying suburbs of Delhi more than three thousand were killed, often by being doused in kerosene and then set alight. They died horrible, macabre deaths. Black burn marks on the ground showed where their bodies had lain. The government—headed by Mrs Gandhi's son Rajiv — remained indifferent, but several citizens' groups came together to provide relief, food and shelter. I was among the hundreds of people who worked in these groups. Every day, while we were distributing food and blankets, compiling lists of the dead and missing, and helping with compensation claims, we listened to the stories of the people who had suffered. Often older people, who had come to Delhi as refugees in 1947, would remember that they had been through a similar terror before. `We didn't think it could happen to us in our own country,' they would say. `This is like Partition again.'

Availability

| KP XXI.000061 | IND I.20 BUT t | My Library | Available |

Detail Information

- Series Title

-

-

- Call Number

-

KP XXI BUT d

- Publisher

- New Delhi : Pengiun Books., 1998

- Collation

-

xi, 371 hlm.; 21 cm

- Language

-

English

- ISBN/ISSN

-

-

- Classification

-

KP XXI

- Content Type

-

-

- Media Type

-

-

- Carrier Type

-

-

- Edition

-

-

- Subject(s)

- Specific Detail Info

-

-

- Statement of Responsibility

-

-

Other version/related

No other version available

File Attachment

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment

Computer Science, Information & General Works

Computer Science, Information & General Works  Philosophy & Psychology

Philosophy & Psychology  Religion

Religion  Social Sciences

Social Sciences  Language

Language  Pure Science

Pure Science  Applied Sciences

Applied Sciences  Art & Recreation

Art & Recreation  Literature

Literature  History & Geography

History & Geography