Text

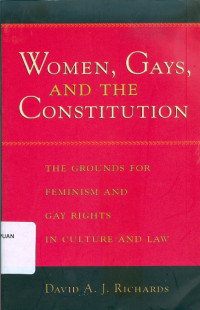

Women, gays, and the constitution: the grounds for feminism and gay rights in culture and law

In this remarkable study, David A. J. Richards combines an interpretive history of culture and law, political philosophy, and constitutional analysis to explain the background, development, and growing impact of two of the most important and challenging human rights movements of our time, feminism and gay rights. Richards argues that both movements are extensions of rights-based dissent, rooted in antebellum abolitionist feminism that condemned both American racism and sexism. He sees the progressive role of such radical dissent as an emancipated moral voice in the American constitutional tradition. He examines the role of dissident African Americans, Jews, women, and homosexuals in forging alternative visions of rights-based democracy. He also draws special attention to Walt Whitman's visionary poetry, showing how it made space for the silenced and subjugated voices of homosexuals in public and private culture. According to Richards, contemporary feminism rediscovers and elaborates this earlier tradition. And, similarly, the movement for gay rights builds upon an interpretation of abolitionist feminism developed by Whitman in his defense, both in poetry and prose, of love between men. Richards explores Whitman's impact on pro-gay advocates, including John Addington Symonds, Havelock Ellis, Edward Carpenter, Oscar Wilde, and André Gide. He also discusses other diverse writers and reformers such as Margaret Sanger, Franz Boas, Elizabeth Stanton, W. E. B. DuBois, and Adrienne Rich. Richards addresses current controversies such as the exclusion of homosexuals from the military and from the right to marriage and concludes with a powerful defense of the struggle for such constitutional rights in terms of the principles of rights-based feminism. Based on close study of the abolitionist movement and expanding on the author's previous books on American revolutionary constitutionalism, Women, Gays, and the Constitution offers interpretive analysis of the Reconstruction Amendments and the promise they hold for gay rights and feminism. Richards founds much of his powerfully felt argument on the broad human rights theories espoused by abolitionist feminists like Lucy Stone, Abby Kelly, and Frederick Douglass, whose radical ideas (some of which influenced the poetry and politics of Walt Whitman) were later repudiated by suffragist feminists, who thought it more expedient to challenge one prejudice at a time. They were similarly rejected by temperance activists like Catharine Beecher and Frances Willard, essentially conservative women who had formed a brief, tempestuous alliance with the suffragists in the decades before the First World War. In resurrecting the writings of these sometimes-obscure political figures to help assess recent Supreme Court verdicts and state legislation, Richards makes a convincing case that "we must identify such dissident interpretive traditions, understand how they achieved such better readings of basic American constitutional principles, and carry this tradition forward today in ways that enable us... to achieve less flawed and more principled interpretations of basic constitutional values. The legal status of lesbians and gay men in contemporary America continues to be controversial, as illustrated by these two very different titles, both by professors of law. Richards aims to combine "interpretive history, political philosophy, and constitutional argument to make sense of the background, development and growing impact of two of the most important movements of human rights currently on the American constitutional scene: feminism and gay rights" and ends by claiming to have explored "the interpretive fertility of antebellum abolition feminism in both the understanding and criticism of contemporary interpretive developments in the areas of gender and sexual preference." His analysis, however cogent, is undermined by a downplaying of lesbians in the title and elsewhere, a problematic conceptualization of "moral slavery," and Richards's often nearly impenetrable prose. In contrast, the rhetorical proposition in the title of Robson's exploration of lesbians and the legal machine is pointedly provocative and witty as well. This challenging collection of 13 essays can be read as a continuation of her previous book, Lesbian (Out)Law: Survival Under the Rule of Law (LJ 6/1/92). Applying queer theory to her examination of the legal system and legal theory to the concept of lesbianism, Robson confronts the complexities of such issues as lesbian identity, class, violence, marriage, and parenting. The writing, a heady mix of pedagogy, lesbian sex, and jurisprudence, is dense and iconoclastic but always intellectually stimulating, ultimately rewarding the reader who perseveres: "But in addition to their danger, both essentialism (modernism) and constructionism (postmodernism) present possibilities for an emancipatory enterprise such as a lesbian legal theory." If 70 pages of endnotes seems excessive, it only reinforces the notion that these titles are intended for subject collections.?Jim Van Buskirk, San Francisco P.L.

Availability

| KP.II.-00025-2 | KP.II RIC W | My Library | Available |

| KP.II.-00025-1 | KP.II RIC W | My Library | Available |

Detail Information

- Series Title

-

-

- Call Number

-

KP.II RIC w

- Publisher

- Chicago : University Of Chicago Press., 1998

- Collation

-

xiv, 531 Hal. ; 23cm.

- Language

-

English

- ISBN/ISSN

-

0-226-712-07-9

- Classification

-

KP.II

- Content Type

-

-

- Media Type

-

-

- Carrier Type

-

-

- Edition

-

-

- Subject(s)

- Specific Detail Info

-

-

- Statement of Responsibility

-

-

Other version/related

No other version available

File Attachment

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment

Computer Science, Information & General Works

Computer Science, Information & General Works  Philosophy & Psychology

Philosophy & Psychology  Religion

Religion  Social Sciences

Social Sciences  Language

Language  Pure Science

Pure Science  Applied Sciences

Applied Sciences  Art & Recreation

Art & Recreation  Literature

Literature  History & Geography

History & Geography